by Niels Lund

No, not the nice kind that fills a boat’s provisioning stores, but the nasty kind comprising lots of twisted wires coming from who-knows-where and possibly leading nowhere, or somewhere impossible to reach. The kind that jams the insides of masts and becomes a bird’s nest behind the switchboard. The kind that has voltage on it, but you have no idea where it gets it from. The kind that has superb timing when failing, such as when you need to get the anchor up quickly, or the AIS to work.

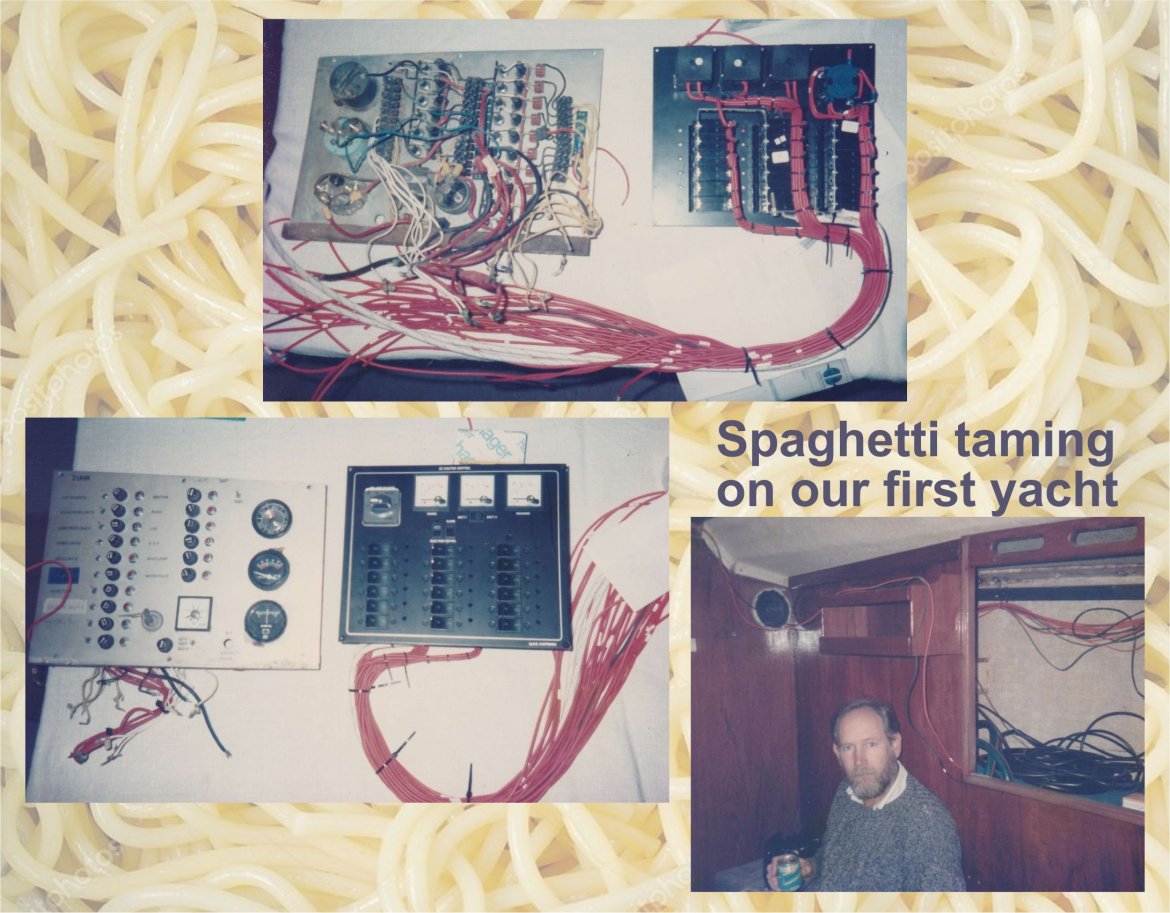

Over time, courtesy of different owners and technicians and the ever-increasing demand for more sophisticated, power-driven equipment, this spaghetti keeps growing. Twenty-two years on three elderly cruising yachts taught me that rewiring a boat is a major task, especially for someone like me, who is not an electrician.

Our first 37-foot yacht had hardly any electrical equipment or electronic gizmos. We were purists in those days – no windlass, no SSB, no AIS, no autohelm, no radar, no computers or cell phones, no wind generator, no fridge/freezer, no watermaker and only one electric pump and one small solar panel – hard to imagine isn’t it? Yet even on that little boat, with only the bare basics, what started out as a simple tidying up job, quickly degenerated from replacing one or two wires to 100% frustration, making me rip everything out, and start again. Having been a boat builder in a previous life, I knew a bit about routing and connecting, but after inserting more than a kilometre of electrical wire and twisting my back and neck, the job eventually got done taking three times longer than expected.

However, when we sailed out of Cape Town heading for the Caribbean, I knew that every wire was 100% sound and neatly labeled, crimped, heat-shrinked and strapped down. There were no hidden breaks or melting crossed lines threatening to leave us in the lurch while maneuvering in tight spaces or wake us up to the nightmare of a smoldering fire.

One of the very few things I prefer about living on land rather than on a yacht, is not crawling into dark, damp, oily places to try and find out which wire disconnected, or climbing up a mast in a howling gale to see which bulb has blown. However, I was mistaken to think I had left electrical problems behind when we moved ashore. My twenty-three-old house is certainly not up to spec in some areas, so here come the electricians and, shortly thereafter, their electrical bills!

On a boat it pays to get rid of all the doubtful spaghetti and use the right tools to make wiring safe and long-lasting. Ancor’s handy mini pocket butane torch (shown in the Bud Tip below), with its windproof and waterproof flame is great for heatshrinking and for sealing synthetic rope ends, or better still a butane soldering kit with hot knife and hot air tools. For testing and tracing voltage, a multi tester and single line remote continuity tester, are essential. A stripper crimper tool is useful for smaller gauge cable. It is also convenient to have a heavy-duty cable cutter and a heavy-duty lug crimper on board for thick battery, windlass, and inverter cables.

circuit tester

continuity tester

soldering kit

crimp tool