By Niels Lund

Rigging is an essential component of a sailing yacht, but it tends to get the least attention. Perhaps because it is often out of sight and therefore out of mind when the boat is anchored, or can look strong, even when it isn’t.

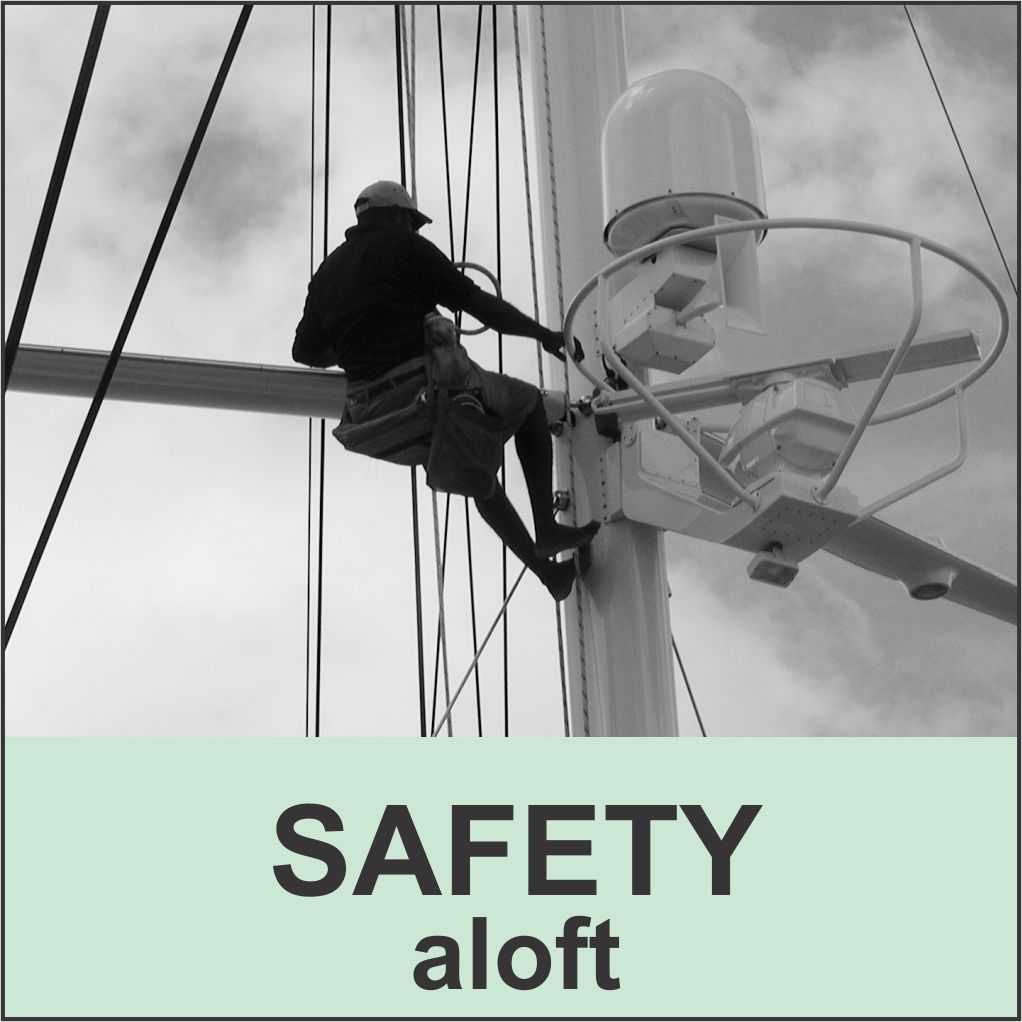

The prospect of going aloft to inspect something you may know little about, but which could have dire consequences should you miss something, can be daunting, resulting in the inspection being delayed until a professional rigger can be contracted to do the job at a cost. Often rig checks get left until required by one’s insurance company, or when something goes seriously wrong in adverse conditions.

While running a rigging company I heard many reasons why rigging should not be replaced, such as:

It looks good – no rust – it must be alright. My previous boat had 20-year-old rigging with no problems. I’ll just replace the shroud that is chafing/fraying/showing minor rusting cracks and do the rest later. It should be done, but I’ll wait until after the racing/sailing season. My boat isn’t insured, so I don’t need to change my rigging yet.

The Caribbean is good for a lot of things, but not for stainless steel. Tropical humidity and heat can be a lethal combination for rigging fittings, especially in places where salt and damp get trapped, such as where fittings are swaged onto the wire, where terminals have been tape-wrapped in such a way as to trap water and deprive the stainless steel of oxygen, preventing passivation and promoting corrosion, and where chain plates go through the deck, or worse, are glassed into the hull. Here are some pointers for keeping your rigging in good condition.

- Routinely rinse off salt build-up on furling systems, sails, rope, shrouds, lifelines and winches with fresh water and a water-soluble detergent, especially after any sailing trip.

- Avoid cleaners containing chlorine, which can destroy stainless steel. Don’t use steel wool or steel scrubbing pads as they can leave minute steel particles embedded in the rigging that will rust.

- Clean, de-oxidize and polish shrouds, remembering to cover your deck and canvas to prevent damage from droplets.

Examine your standing rigging regularly with a magnifying glass (including sheaves, sheave boxes, bushes, pins, retaining brackets, spreaders, spreader tips and shroud tangs). Keep an eye out for corrosion, pitting, cracks, broken strands or “meat hooks”, discoloration or rust spots. Areas showing rust should be thoroughly cleaned and inspected to see if there is a hairline crack, or metal crystallization. Tip: Sometimes a broken strand can be identified by looking down (or up) the wire. If a strand is broken the cable will get a slightly asymmetrical look, i.e. not perfectly round in cross-section.

Below is a suggested checklist:

- Hound (Mast) S/S Plates: If bright and shiny with no rust stains, or just slightly rusty in places (light brown) – they should be okay. However, if areas have local, darker stains/lines, then inspect with a magnifying glass. Look carefully for signs of hairline cracks. Any sign of very dark/black spots indicates that something is going on inside the fitting.

- Hounds Thru Bolts: Check nuts for rust. Thru bolts will probably be 316 S/S, but the nuts are often 304 S/S, and these will rust much faster than 316 S/S. If showing dark stains/cracks – replace.

- Clevis and Cotter Pins: If showing signs of dark rust – replace. Keep the toggle or turnbuckle fork evenly spaced on the chain plate or shroud tang, using stainless steel washers.

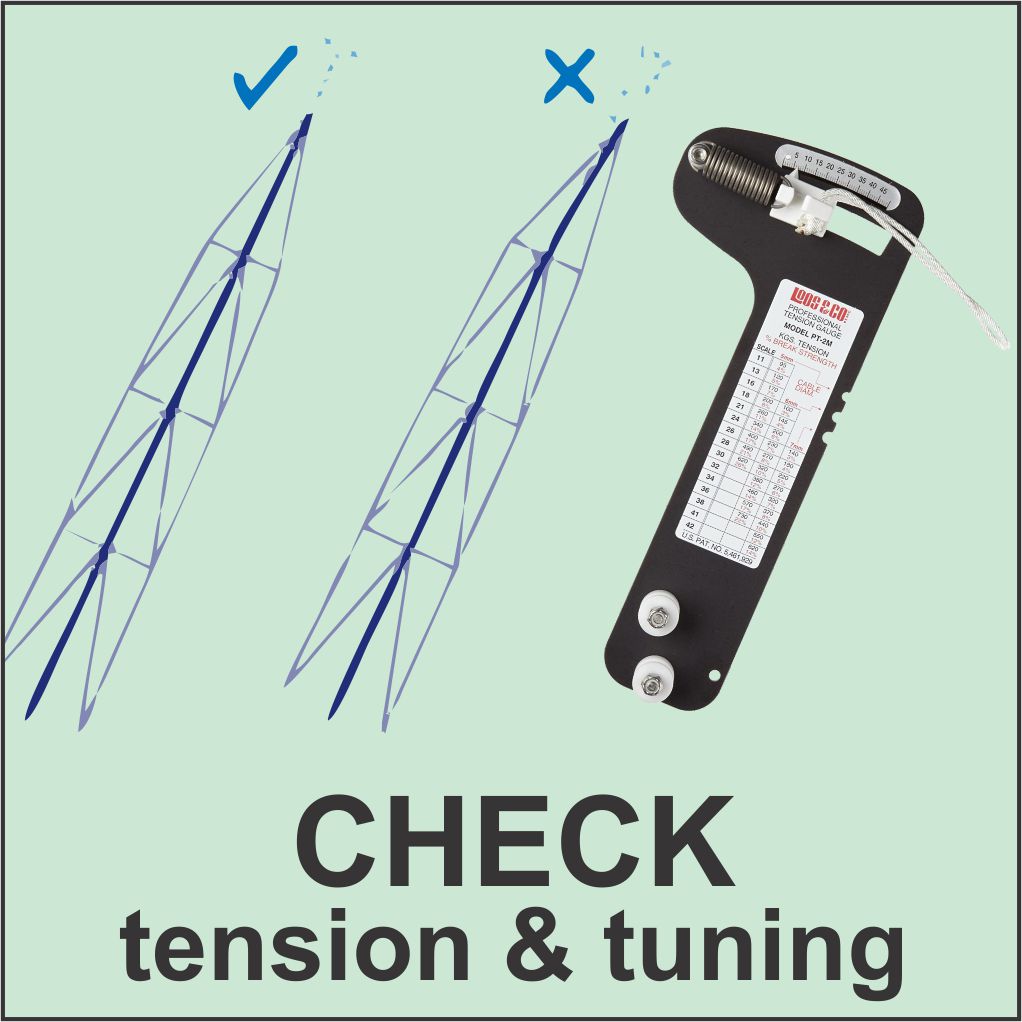

Be aware that, unlike corrosion, fatigue-related problems cannot be detected visually. This problem is discussed further under tension and tuning.

Rigging Wire Quality: Over the last 25 years, due to rising costs, the Chrome and Nickel content of 316 S/S used in marine rigging has been decreased. The alloy still meets the specification of 316 S/S, but is closer to the 304 S/S spec. This is why newer cables may rust quicker than older cables and show higher magnetic properties. However, this should not cause undue concern.

Make sure your standing rigging is tensioned correctly. Fatigue, which is determined by the number of bending cycles to which a piece of wire or hardware has been subjected, is a matter for concern. Slack rigging is especially bad, as the wire vibrates or moves much more than when the wire is taut, subjecting it to a lot of reversing movement relative to the swage. This causes fatigue failure at, or just inside, the swage. Insert a very thin screwdriver between the strands to detect a broken strand. Tuning the rig correctly keeps the mast in column and prevents the rigging from moving around too much. Shiny new stainless steel shrouds that are slack can be more dangerous than rusty wires tuned correctly.

Also check all hardware, including shackles, for hairline cracks, corrosion, or deformation. A missing cotter pin, release pins that no longer release and rope that is poorly spliced, fatigued, frayed or damaged can all compromise sailing performance and safety. Take a picture of anything questionable and email it to your rigger, so that together you can resolve any problems.

- For better confidence aloft, buy yourself the strongest, most comfortable bosun’s chair you can afford, preferably with shoulder straps to prevent you from falling out should the seat invert, spacious pockets to hold tools with Velcro closing flaps, and cord attachment points to tie tools so they can’t drop onto anyone below. Store it in a readily accessible, dry locker and have it restitched and reinforced by a sailmaker when necessary.

- Make sure your halyards are always in good condition, so as not to pose a threat to anyone using them to climb the mast.

- Train your crew to haul you up safely, holding the line at least 12 inches away from the winch to ensure that fingers cannot be drawn into the winch drum coils.

- Keep constant watch on deck while someone is aloft. Don’t do what one fed-up cruising wife claims she did – she left her poor husband up there and went below, ignoring his calls to let him down “to teach him a lesson”!

An elderly customer, previously a hotshot racing skipper, asked me to “geriatricize” his yacht by taking all lines back to the cockpit to reduce time spent crawling around a bouncing foredeck. However, even if you are a fit young cruiser, easily accessible line controls, asound furling system and sturdy mast steps are all great safety devices.

Take the recommended period for replacing rigging seriously and have your rig checked before racing competitively, or undertaking long passages. In the Caribbean, to be sure of timeous professional service, schedule your rig work well in advance to avoid lengthy waits during rush periods dictated by sailing and hurricane seasons on the islands.

Finally, read the small print regarding weight restrictions when attaching a heavy communication pod/radar/wind vane to your mast. We learnt this the hard way one night when in rough weather the newly installed wind generator bracket on the mizzen mast broke partly loose. The wildly spinning windvane swung around dangerously above our crew-filled cockpit, requiring me to climb up to lasso and lower it before the wind could rip it right off and dump it on us. Re-reading the wind generator installation instructions I realised we had not noticed the last sentence: “Do not install on a mizzen mast.” A heavy object attached high up has an adverse effect on the yacht’s heeling moments and can overstress the mast at the bracket connection point.

Bottom line for safe, carefree sailing: clean, protect, inspect and replace your rigging when necessary. Believe that rigging matters, and act accordingly!